While attempting to obtain routine dental care for the first time in three years, I encountered a situation that compelled me to leave before we even got to tilting the exam chair back. What happened wasn’t on my radar; not even close. In fact, I was actually excited to go to the dentist, especially to get a good cleaning. I have always liked my dentists, I used to receive care every six months, and have usually had nothing but positive experiences in very clean environments. After a couple days of processing this recent ordeal, I’m almost certain I blatantly ignored the warning signs as a result of several different factors.

It was an experience that many disabled and chronically ill people have had, probably far more than once. Those of us who have been disabled since birth/childhood have typically experienced this throughout our whole lives:

Someone on the “care team” side tarnishes the appointment by senselessly trying to satisfy their personal curiosities about your disabilities, and only your disabilities— often while using ableist language.

They want to know all about what you can and can’t do, regardless of its relevance to dental health or what you’ve entered in on your forms. If you’re able to work or go to school, then they want to know if you have to do it at home, or if you can actually leave the house (how do you think I got here, and why does it matter?). But don’t forget, “Disability Advocacy,” apparently isn’t a ‘real job’ and they will likely gloss over it. Medical questionnaires that you’ve filled out honestly and seriously, somehow prompt quips from so-called ‘professionals’ such as, “You’re too young to have all this going on!”

I just turned 31. People in every medical field have been saying this to me since I was 6 years old. Why on earth is someone who can’t be a day over 35 (if not younger than me) saying this to me? If this dental hygienist was truly just trying to get to know me, there were plenty of other topics and questions she could have used instead. Who actually wants to talk about work while they’re -usually- taking time away from work to be at the dentist? Per my prior experiences, dental hygienists are usually pretty skilled in the art of casual conversation, but perhaps this was a student who needed some extra training; that detail is still unclear to me.

As if that wasn’t frustrating enough, cue my OCD symptoms and a panic attack being triggered by having to ask the hygienist to wear her mask on her face instead of around her neck when our faces were so close together (Chris and I both still mask in public because I’m immunocompromised, and Covid is still very much relevant), dirty x-ray equipment, an air freshener I’m allergic to plugged in right next to the x-ray equipment, the feeling of passing out from being positioned so awkwardly and my MCAS flaring from the chemical fragrance next to me, and then a grotesquely disgusting fabric-lined blood pressure wrist cuff that hadn’t been cleaned in who knows how many eons being placed on my eczema-laden arm. It was overwhelming beyond belief. I wanted to crawl out of my skin, prompting my partner to jump into action to help protect me from myself when we got home.

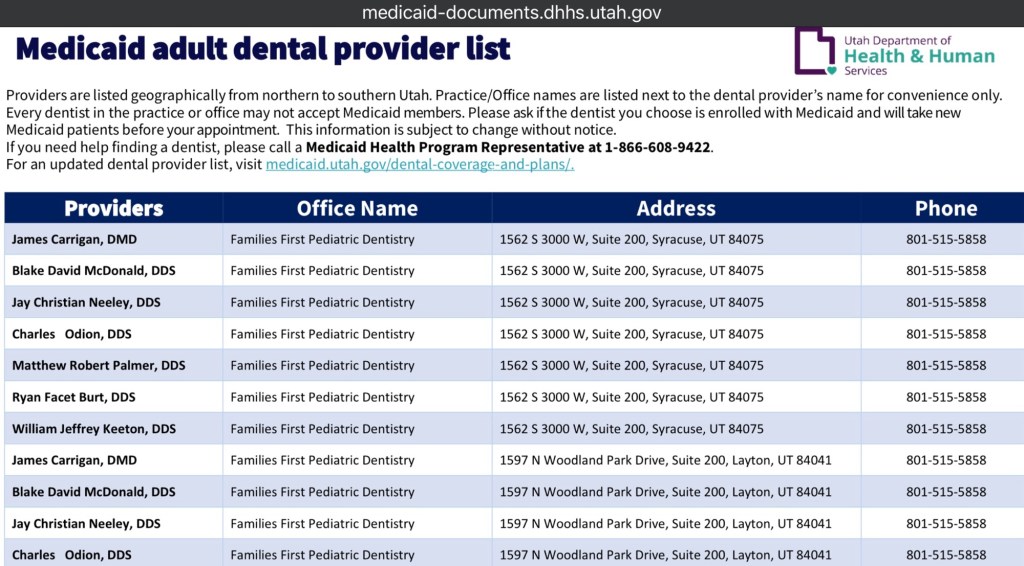

The final straw was the dental hygienist interrupting my medical concerns about my teeth to say something about teeth whitening and cosmetics. I am a Medicaid recipient and was there for a Medicaid appointment. I found their dental clinic via the Utah Department of Health & Human Services website’s PDF list. I won’t get into the specifics on why teeth whitening is a gimmick, but Medicaid doesn’t cover whitening or other cosmetic procedures. It won’t even cover braces for urgent medical necessity. Cosmetics and appearance are a huge part of mental wellness, yes. But I don’t have that luxury -even if I wanted it- because of my insurance’s limitations, and it raised a red flag about what other services they’re dangling in front of disabled patients like a carrot when they should know it’s likely out of reach for many of us.

I very politely said I felt uncomfortable and that I didn’t want to continue the appointment when all that’s being discussed are my disabilities. I was not there for her entertainment, to pique any curiosities, or to be made to feel like a sideshow. I wasn’t there to purchase services outside the ones my insurance covers, nor to hear pitches about them. I was there to receive professional services; x-rays, cleaning, exam. That was apparently too boring to focus on, and I have personally grown very tired of being used by people within the medical system. So, I left. Contrary to what some insurance companies may say, dentistry is absolutely a part of the medical/healthcare system, and oral healthcare is essential to whole-body wellness.

Upon my getting up to leave, the dental hygienist was stunned and apologizing for, “trying to get to know [me].” Despite this, she closely followed us out to the front desk and loudly proclaimed, “You can leave.” Thank you, I was quite literally already on my way out. I was simply making sure that reception was on the same page about why I was leaving, that I was not canceling, and that I would not be charged for services not rendered. It was an extremely peaceful exit on my behalf, particularly considering the amount of disrespect that had been slung my way.

I’ll be the first to admit that they gave a horrible first impression in the parking lot and entry route. Not only was the access aisle for the only accessible parking space (also outside of technical specifications) blocked off with landscaping rocks, the ramp to get into the building was far too steep. These issues forced me to use my cane instead of my wheelchair. Still, I gave them the benefit of the doubt anyway, because I was just excited to receive care. And in all reality, I think we as a collective disabled Community give the benefit of the doubt to people within those systems all the time because that care can be incredibly difficult to find in the first place.

It’s not like I didn’t do some serious research beforehand. Most of us do. Hours upon hours of it. I knew the dentistry location was newer within the last few months and housed inside an older residence-turned-commercial to accommodate prior businesses. It was clear that the dentistry clinic had recently renovated, and it appeared from the limited Google Earth & Maps images as though they had an accessible parking space and entry.

What I couldn’t see was the ramp’s ridiculously steep slope; there were no photos. How could I have possibly predicted that on the one day I go to visit, there would be a pile of landscaping rocks in the access aisle? There were no interior photos of their new location, so I couldn’t have known the exam room wouldn’t accommodate my wheelchair, even if I had been able to use it outside, on the entry route, and in the waiting room. When I asked about how they would’ve done the around-the-head x-rays if I had been using my wheelchair, she merely laughed and moved on to the next question about cardiac conditions.

I also would have loved to have been informed in-advance that there would be several pages of paperwork to fill out. Waiting to do so until the patient arrives to their appointment is not ideal. Had I not brought my partner with me, I would have had to ask for the clinic staff’s help to fill out the forms. My hands can’t always hold a pen, and I’m far from being alone in that. It is incredibly helpful when patients have the option to fill forms out ahead of time— either online, via email, fax, snail mail, etc.

When I contacted Utah Department of Health and Human Services (UDHHS) to report the accessibility issues and encourage this clinic’s removal from the list until the accessibility issues could be resolved and sensitivity training addressed, I was told that they can’t do anything about it. Allegedly, University of Utah School of Dentistry provides the list for the Medicaid Dental Provider Directory PDF that is listed on UDHHS’ website. UDHHS truly believes that they cannot edit a PDF that has their logo all over it and is on their own website. I was advised to reach out to U of U, and when I informed her that U of U cannot edit a PDF on UDHHS’ website, I was met with ire. I asked to speak to a supervisor and eventually was told I would receive a call back before the end of the day. Predictably, I still have not received a call back.

Utah Medicaid recipients like myself are forced to use the Medicaid Dental Provider Directory in order to find a dentist who can provide covered care. Despite how important it is for a list like this to be accurate and remain up to date, we are told by Medicaid representatives to call every clinic on the list to make sure they are still with the program. In doing so, I frequently ran into issues where listed dentists and clinics were no longer enrolled in the program. A majority of these clinics had already reached out to U of U and UDHHS to be removed from the list, but were indeed on the list and still received frequent calls from patients seeking care that they inevitably have to turn away. Further, many of the listed providers on the ‘Medicaid Adult Dental Provider List’ are Pediatric Dentistry clinics, leading to a great deal of confusion for both patients and providers. Add in the limited number of providers on the list for any given city outside of Salt Lake City, and you’ve got woefully limited options.

When you’re finally able to narrow down the list to find your available options, then it’s off to Google and other related tools to research whether or not the clinic is accessible. Gotta take a gander at the parking lot or how close the bus stop is, the building layout, if there’s an accessible route to the entrance, interior photos, reviews…

It’s far from being a dramatic step to take— I still have yet to find a dermatology clinic in Utah that actually meets ADA Minimum Standards and doesn’t use an obscene amount of chemical air fresheners; I’ve been searching for over a year while being able to cast a much wider net than with dentistry.

This doesn’t even begin to cover overall reviews, and other factors one might need to consider, such as: languages spoken, interpreting availability, gender of the provider, 2SLGBTQIA+ safeness, and more. If a dentist on the list has 2.5 stars out of 5 and doesn’t look accessible from the photos, why would one bother? Some of the reviews of clinics listed on the Directory specifically mentioned unsupervised dentistry students causing long term complications and severe pain. Others mentioned program issues, billing issues, and ambiguous charges. All things that any reasonable person seeking care would steer away from.

The ‘No Surprises Act’ has specific requirements for health plans regarding provider directories, primarily focusing on accuracy and accessibility. Plans must verify and update their directories at least every 90 days, promptly update information upon notification from providers, and have procedures for removing providers with unverifiable information. Additionally, plans must respond to patient requests about a provider’s network status within one business day and maintain records of these communications for two years. However, these requirements typically do not apply to Medicaid.

It shouldn’t be this difficult to find and receive dental care, or any healthcare for that matter. But this is the unfortunate reality for countless people in Utah, and far beyond. Even Washington State’s Medicaid services led myself and other patients astray on a frequent basis with outdated provider lists/directories. Efforts to correct these lists or report issues are met with a, “not my problem” kind of mentality by the very entities issuing the lists, and often, the same ones paying for the services.

This has been a well-documented issue (see: This study published in AJMC, NBC’s take on “Ghost Networks”, and ProPublica’s telling of Ravi Coutinho’s story & the tragic follow up) across many states, but I have yet to see forward progress in addressing the root of the problem in a meaningful way. The practice has become such a prolific problem that it’s been given the nickname “ghost networking”. It’s killing people in our Community— people like Ravi Coutinho, and we won’t ever let that go. Access to care has to be seriously addressed within every specialty and across every healthcare entity, private and public. Our very lives depend on it.

Leave a comment